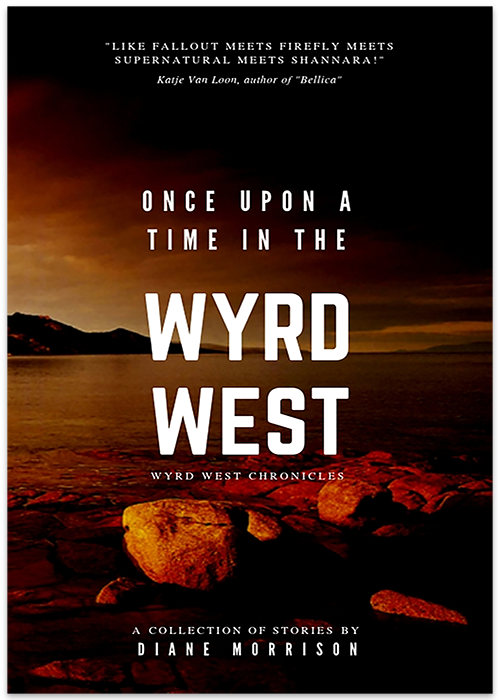

Once Upon a Time in the Wyrd West

Table of Contents

Front Matter BOOK 1: SHOWDOWN Last Stand The Signpost Smelling Trouble Answering the Call Slinger's Apprentice Pine Boxes Baptism of Fire Showdown Dead Book BOOK 2: VICE & VIRTUE Coffee The Posse Nightfall Gunslinger's Work Marks of Cain BOOK 3: THE VIGIL The Posse Splits Up On the Road Laughing Bear Nightmares Home The Lodge The River Unquiet Dead The Vigil BOOK 4: WAY OF THE GUN Waiting Celebration Too Quiet Bandits Hide-and-Seek Getting Help Thunderstorm Rumble in the Kitchen Slingers Always Get the Chance BOOK 5: THE REAPING The Posse Rides Shooting Gallery Gadgets and Specters Dowsing Dusk Falls The Cotton Candy Man It Never Is BOOK 6: THE WIDOW'S GAMBIT The Widow A Message Northern Lights Blood Magic The Courtesan Single-Malt and Cigar Ghosts of Murdered Children Red-Eye Outpost Spectres The Judge The Apprentice The Fence A Gunslinger's Gift ~About the Author~ ~Also by the Author~Slinger's Apprentice

His father had shown him the craft and the trade. His tanned, calloused, thick-fingered hands guided Graeme’s alabaster, fine-boned fingers. First, you broke open the chamber and you removed the cartridges. Then you oiled and swabbed the barrels and the pins. Then you polished the barrels until they shimmered blue. You wiped off the excess. You buffed the heavy wooden grips to a rich chocolate gleam. You loaded the cartridges with their blessed bullets one at a time until all six were in chamber. You snapped the cylinders into place. Then you aimed as if you would fire, hovering your fingers over the triggers. Then you broke the revolvers down and did it again.

You never fired those revolvers, not unless you meant to kill someone. You practiced with lesser handguns of plastic and metal, made in the latter days of the Ancients. You learned to aim with the power of will through the sights of your eyes. You learned to kill in your head before you did it with your hand. Again, and again, loading and reloading, until fine-boned hands carried the same callouses as his father’s. Rough pressure callouses on the index finger, inside of the knuckles and heels of his hands from the repetition. Prints burned away from loading and reloading cartridges into hot cylinders.

He could shoot almost before he was out of diapers. He could shoot birds out of the sky while riding by the time he started school. He could group every one of those bullets in a bullseye at a hundred yards by the time he started having naughty dreams about his schoolmarm. Now he could draw and replace those pistols in their holsters before anyone even heard the shot ring out. He could shoot out a deer’s eyes at a hundred and twenty-five yards.

Later his father had taught him the craft of munitions. Alchemy to create the powder: how to distill saltpeter from piss, which was a cherished commodity, especially in the Windpan. All charcoal was carefully preserved in pouches until it could be ground up with the extracted saltpeter and sulphur. Three separate mortars and pestles, packed away with the molds, to powder each component. That way, the time they spent blended together and exposed to the open air was minimal.

Safety procedures and protective prayers frightened into him at about the time other children learn nursery rhymes. The uncle who died of sulphur poisoning. The friend who died in an explosion. The blessings incanted over the sacred alchemical blend as it was loaded into the cartridges. How to smelt the metal, pour the bullets, and etch the mystic signs into them so they would fly true. Sitting together in the evening and pouring bullets while his mother played piano, drawing enchantment from the keys and singing in her ethereal sidhe voice. Sometimes he would sing along. He especially liked the sacred hymns and he learned to play them on the guitar, staying up late to practice them in secret, just as his little sister studied the forbidden Gunslinger arts. Sometimes his singed fingers bled on the strings, but their parents didn’t seem to notice.

Gunslinger lore held that once things had been different. Once, chemical processes were reliable and predictable. Guns and munitions were produced in factories; or so they said. But that was before the Cataclysm.

His father told him of his duty. “The only thing that stops a Gunslinger from bein’ an Outlaw is his honour,” he explained when Graeme was still very small. The cartridges in his gunbelt twinkled like stars in the blue glow of the voltaic lamp. A Mark of Cain darkened his forehead, so he must have made a kill recently. Graeme considered his father’s craggy, sundried face with its solemn blue eyes and nodded just once. He sensed this was very serious.

But perhaps Colin Walsh sensed that his son did not understand. “Hear me, boy,” the Gunslinger sighed. “Killin’ hurts the soul. That’s why we do it; so no one else has to. But that don’t mean it don’t hurt your soul, just ‘cause you’ll be a Slinger.”

“Is that why we do the Purification?” Graeme had asked.

Colin Walsh nodded. “But that ain’t enough to keep your hands clean, boy. B ‘fore you draw, be sure there ain’t nothin’ else to be done but draw. And when you do, do it right. Do it clean and honourable. And never forget to record the name in your Dead Book –” he put his hand on his breast pocket, where the edge of a tattered notebook peered over the hem – “‘cause you’ll be called to Accountin’ when the Lord comes to bring you home to the Lady.”

“I want to be a Gunslinger too,” Piper pouted. She had been hardly more than a baby then, still with baby-fat cheeks.

Their father touched one of them with his rough fingers. “No, you don’t,” he said. His eyes were sad then; not fierce as they usually were, nor gunmetal grey, like when the guns he slung on his hips were in his hands instead. “I wish it weren’t Graeme’s Fate neither. A Gunslinger’s road is paved with bullets and blood. Be glad you ain’t Called to walk that path.”

Piper nodded solemnly, though her eyes simmered with rebellion.

But their father relented. “Right then, let’s leave it alone for now. Go to sleep, Piper.”

As usual, Piper tried to bargain. “But Papa, will you tell us about Gaddy and Racette again?” The Book of Sinners said that those blackhats had been hung right in Queenstown. Piper never tired of the tale of the manhunt.

“Tomorrow,” their father promised as he leaned over and kissed her on the cheek.

Piper tittered, “It tickles!”

“Does it now,” said their father, and he promptly seized his daughter and rubbed her face with his road-bristled chin. She giggled and kicked.

Graeme didn’t feel it was at all fair that he was Called to be a Gunslinger and Piper was not, because her spirit was more adventurous than his own. She would come and watch him at target practice, her blue eyes sparkling their plea at him. So, in secret he taught her the ritual of the Devotionals, the breaking down and the cleaning, the loading, and the forging. When they were older, he would say they were going hunting – that was permitted – and together they would ride out into the desert and practice shooting with their rifles. And if anyone ever wondered why they never brought home any game, they never said a word about it.